Kevin St Clair's religious beliefs of the Holy Bible

Monday, September 16, 2013

I am Catholic

As I have always been very fond of of the Patriarch Saint Nicholas, better known as Santa Clause, I have always leaned toward the Catholic faith of the European Crusades.

Sunday, March 17, 2013

Inheritance in the kingdom of Christ and of God. Ephesians 5

Ephesians 5

1 Be ye therefore followers of God, as dear children; 2 And walk in love, as Christ also hath loved us, and hath given himself for us an offering and a sacrifice to God for a sweetsmelling savour. 3 But fornication, and all uncleanness, or covetousness, let it not be once named among you, as becometh saints; 4 Neither filthiness, nor foolish talking, nor jesting, which are not convenient : but rather giving of thanks. 5 For this ye know , that no whoremonger, nor unclean person, nor covetous man, who is an idolater, hath any inheritance in the kingdom of Christ and of God. 6 Let no man deceive you with vain words: for because of these things cometh the wrath of God upon the children of disobedience. 7 Be not ye therefore partakers with them. 8 For ye were sometimes darkness, but now are ye light in the Lord: walk as children of light: 9 (For the fruit of the Spirit is in all goodness and righteousness and truth;) 10 Proving what is acceptable unto the Lord. 11 And have no fellowship with the unfruitful works of darkness, but rather reprove them. 12 For it is a shame even to speak of those things which are done of them in secret. 13 But all things that are reproved are made manifest by the light: for whatsoever doth make manifest is light. 14 Wherefore he saith , Awake thou that sleepest , and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give thee light . 15 See then that ye walk circumspectly, not as fools, but as wise, 16 Redeeming the time, because the days are evil. 17 Wherefore be ye not unwise, but understanding what the will of the Lord is. 18 And be not drunk with wine, wherein is excess; but be filled with the Spirit; 19 Speaking to yourselves in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing and making melody in your heart to the Lord; 20 Giving thanks always for all things unto God and the Father in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ; 21 Submitting yourselves one to another in the fear of God. 22 Wives, submit yourselves unto your own husbands, as unto the Lord. 23 For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church: and he is the saviour of the body. 24 Therefore as the church is subject unto Christ, so let the wives be to their own husbands in every thing. 25 Husbands, love your wives, even as Christ also loved the church, and gave himself for it; 26 That he might sanctify and cleanse it with the washing of water by the word, 27 That he might present it to himself a glorious church, not having spot, or wrinkle, or any such thing; but that it should be holy and without blemish. 28 So ought men to love their wives as their own bodies. He that loveth his wife loveth himself. 29 For no man ever yet hated his own flesh; but nourisheth and cherisheth it, even as the Lord the church: 30 For we are members of his body, of his flesh, and of his bones. 31 For this cause shall a man leave his father and mother, and shall be joined unto his wife, and they two shall be one flesh. 32 This is a great mystery: but I speak concerning Christ and the church. 33 Nevertheless let every one of you in particular so love his wife even as himself; and the wife see that she reverence her husband.

Friday, March 8, 2013

Nicene Creed

Nicene Creed

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

| Nicene Creed | |

| Created | 381 |

| Author(s) | First Council of Constantinople |

| Read online | Nicene Creed at Wikisource |

The Nicene Creed has been normative for the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox churches, the Anglican Communion, and many Protestant denominations, forming the eponymous mainstream definition of Christianity itself in Nicene Christianity.[2]

The Apostles' Creed, which in its present form is later, is also broadly accepted in the West, but is not used in the East. One or other of these two creeds is recited in the Roman Rite Mass directly after the homily on all Sundays and Solemnities (Tridentine Feasts of the First Class). In the Byzantine Rite Liturgy, the Nicene Creed is recited on all occasions, following the Litany of Supplication.

In the Roman Catholic Church, the Nicene Creed is part of the profession of faith[3] required of those undertaking important functions within the Church.[4]

For current English translations of the Nicene Creed, see English versions of the Nicene Creed in current use.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] Nomenclature

There are several designations for the two forms of the Nicene creed, some with overlapping meanings:- Nicene Creed or the Creed of Nicaea is used to refer to the original version adopted at the First Council of Nicaea (325), to the revised version adopted by the First Council of Constantinople (381), to the Latin version that includes the phrase "Deum de Deo" and "Filioque",[5] and to the Armenian version, which does not include "and from the Son", but does include "God from God" and many other phrases.[6]

- Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed can stand for the revised version of Constantinople (381) or the later Latin version[7] or various other versions.[8]

- Icon/Symbol of the Faith is the usual designation for the revised version of Constantinople 381 in the Orthodox churches, where this is the only creed used in the liturgy.

- Profession of Faith of the 318 Fathers refers specifically to the version of Nicea 325 (traditionally, 318 bishops took part at the First Council of Nicea).

- Profession of Faith of the 150 Fathers refers specifically to the version of Constantinople 381 (traditionally, 150 bishops took part at the First Council of Constantinople).

[edit] History

The purpose of a creed is to act as a yardstick of correct belief, or orthodoxy. The creeds of Christianity have been drawn up at times of conflict about doctrine: acceptance or rejection of a creed served to distinguish believers and deniers of a particular doctrine or set of doctrines. For that reason a creed was called in Greek a σύμβολον (Eng. sumbolon), a word that meant half of a broken object which, when placed together with the other half, verified the bearer's identity. The Greek word passed through Latin "symbolum" into English "symbol", which only later took on the meaning of an outward sign of something.[9]The Nicene Creed was adopted in the face of the Arian controversy. Arius, a Libyan presbyter in Alexandria, had declared that although the Son was divine, he was a created being and therefore not co-essential with the Father, and "there was when he was not,"[10] This made Jesus less than the Father, which posed soteriological challenges for the nascent doctrine of the Trinity.[11] Arius's teaching provoked a serious crisis.

The Nicene Creed of 325 explicitly affirms the co-essential divinity of the Son, applying to him the term "consubstantial". The 381 version speaks of the Holy Spirit as worshipped and glorified with the Father and the Son. The Athanasian Creed describes in much greater detail the relationship between Father, Son and Holy Spirit. The Apostles' Creed makes no explicit statements about the divinity of the Son and the Holy Spirit, but, in the view of many who use it, the doctrine is implicit in it.

[edit] The original Nicene Creed of 325

Main article: First Council of Nicaea

The original Nicene Creed was first adopted in 325 at the First Council of Nicaea. At that time, the text ended after the words "We believe in the Holy Spirit", after which an anathema was added.[12] (For other differences, see Comparison between Creed of 325 and Creed of 381, below.)The Coptic Church has the tradition that the original creed was authored by Pope Athanasius I of Alexandria. F. J. A. Hort and Adolf Harnack argued that the Nicene creed was the local creed of Caesarea (an important center of Early Christianity) brought to the council by Eusebius of Caesarea. J.N.D. Kelly sees as its basis a baptismal creed of the Syro-Phoenician family, related to (but not dependent on) the creed cited by Cyril of Jerusalem and to the creed of Eusebius.

Soon after the Council of Nicaea, new formulae of faith were composed, most of them variations of the Nicene Symbol, to counter new phases of Arianism. The Catholic Encyclopedia identifies at least four before the Council of Sardica (341), where a new form was presented and inserted in the Acts of the Council, though it was not agreed on.

[edit] The Niceno–Constantinopolitan Creed of 381

The traditional belief is that the Second Ecumenical Council held in Constantinople in 381 added the section that follows the words "We believe in the Holy Spirit" (without the words "and the Son" relative to the procession of the Holy Spirit, which would become a point of contention in the Great Schism of Orthodoxy from Catholicism);[13] hence the name "Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed", referring to the Creed as modified in the First Council of Constantinople.This is the received text of the Eastern Orthodox Church,[14] with the exception that in its liturgy it changes verbs from the plural by which the Fathers of the Council collectively professed their faith to the singular of the individual Christian's profession of faith. Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Churches use exactly the same form of the Creed, since the Catholic Church teaches that it is wrong to add "and the Son" to the Greek verb "ἐκπορευόμενον", but correct to add it to the Latin "qui procedit", which does not have precisely the same meaning.[15]

By the end of the nineteenth century,[16] doubt has been cast on this explanation of the origin of the familiar Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed (C), commonly called the "Nicene Creed". On the basis of evidence both internal and external to the text, it has been argued that this creed originated not as an editing by the First Council of Constantinople of the original Creed proposed at Nicea in 325 (N), but as an independent creed (probably an older baptismal creed) modified to make it more like N and attributed to the Council of 381 only later.[17] A key point in this argument was the fact that C was first quoted at the Council of Chalcedon in 451.[16] While it is generally agreed that C is not a modification of N, serious objections were voiced to the claim that no new credal formula was approved by the Council in 381, and in 1950 Kelly proposed a solution which covered all the objections.[16]

The third Ecumenical Council (Council of Ephesus of 431) reaffirmed the original 325 version[18] of the Nicene Creed and declared that "it is unlawful for any man to bring forward, or to write, or to compose a different (ἑτέραν – more accurately translated as used by the Council to mean “different,” “contradictory,” and not “another”)[19] faith as a rival to that established by the holy Fathers assembled with the Holy Ghost in Nicæa" (i.e. the 325 creed)[20] This statement has been interpreted as a prohibition against changing this creed or composing others, but not all accept this interpretation.[21] This question is connected with the controversy whether a creed proclaimed by an Ecumenical Council is definitive or whether additions can be made to it.

[edit] Comparison between Creed of 325 and Creed of 381

The following table, which indicates by [square brackets] the portions of the 325 text that were omitted or moved in 381, and uses italics to indicate what phrases, absent in the 325 text, were added in 381, juxtaposes the earlier (325 AD) and later (381 AD) forms of this Creed in the English translation given in Schaff's work, Creeds of Christendom.[22]| First Council of Nicea (325) | First Council of Constantinople (381) |

|---|---|

| We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible. | We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. |

| And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father [the only-begotten; that is, of the essence of the Father, God of God], Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father; | And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds (æons), Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father; |

| By whom all things were made [both in heaven and on earth]; | by whom all things were made; |

| Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down and was incarnate and was made man; | who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man; |

| He suffered, and the third day he rose again, ascended into heaven; | he was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered, and was buried, and the third day he rose again, according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of the Father; |

| From thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead. | from thence he shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; |

| whose kingdom shall have no end. | |

| And in the Holy Ghost. | And in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of life, who proceedeth from the Father, who with the Father and the Son together is worshiped and glorified, who spake by the prophets. |

| In one holy catholic and apostolic Church; we acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; we look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen. | |

| [But those who say: 'There was a time when he was not;' and 'He was not before he was made;' and 'He was made out of nothing,' or 'He is of another substance' or 'essence,' or 'The Son of God is created,' or 'changeable,' or 'alterable'—they are condemned by the holy catholic and apostolic Church.] |

[edit] Filioque controversy

Main article: Filioque

In the late sixth century, the Latin-speaking churches added the words "and from the Son" (Filioque) to the description of the procession of the Holy Spirit, in what Easterners have argued is a violation of Canon VII of the Third Ecumenical Council, since the words were not included in the text by either the Council of Nicaea or that of Constantinople.[23]The Vatican has recently stated that, while these words would indeed be heretical if associated with the Greek verb ἐκπορεύεσθαι of the text adopted by the Council of Constantinople,[15] they are not heretical when associated with the Latin verb procedere, which corresponds instead to the Greek verb προϊέναι, with which some of the Greek Fathers also associated the same words.[15] Latin has no word with the same overtones as ἐκπορεύεσθαι (ἐκπορευόμενον, in the original Greek text of the Creed, is the present participle of this verb), and in its translation can only use the verb procedere, which is broader in meaning.

[edit] Views on the importance of this creed

The view that the Nicene Creed can serve as a touchstone of true Christian faith is reflected in the name "symbol of faith", which was given to it in Greek and Latin, when in those languages the word "symbol" meant a "token for identification (by comparison with a counterpart)",[24] and which continues in use even in languages in which "symbol" no longer has that meaning.In the Roman Rite Mass, the Latin text of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, with "Deum de Deo" (God from God) and "Filioque" (and from the Son), phrases absent in the original text, was previously the only form used for the "profession of faith". The Roman Missal now refers to it jointly with the Apostles' Creed as "the Symbol or Profession of Faith or Creed", describing the second as "the baptismal Symbol of the Roman Church, known as the Apostles' Creed".[25] The liturgies of the ancient Churches of Eastern Christianity (Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, Assyrian Church of the East) and the Eastern Catholic Churches), use the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, never the Western Apostles' Creed.

In the Byzantine Rite Liturgy, the Creed is typically recited by the cantor, who in this capacity represents the whole congregation. Many, and sometimes all, members of the congregation join the cantor in rhythmic recitation. It is customary to invite, as a token of honor, any prominent lay member of the congregation who happens to be present (e.g. royalty, a visiting dignitary, the Mayor, etc.) to recite the Creed instead of the cantor. This practice stems from the tradition that the prerogative to recite the Creed belonged to the Emperor, speaking for all his people.

Some evangelical and other Christians consider the Nicene Creed helpful and to a certain extent authoritative, but not infallibly so in view of their belief that only Scripture is truly authoritative.[26][27] Other groups, such as the Church of the New Jerusalem, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the Jehovah's Witnesses explicitly reject some of the statements in the Creed.[28][29][30][31]

[edit] Ancient liturgical versions

All ancient liturgical versions, even the Greek, differ at least to some small extent from the text adopted by the First Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople.| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The Latin text, as well as using the singular, adds "Deum de Deo" (God from God) and "Filioque" (and from the Son) to the Greek. On the latter see The Filioque Controversy above. Inevitably also, the overtones of the terms used, such as "παντοκράτορα" (pantokratora) and "omnipotentem" differ ("pantokratora" meaning Ruler of all; "omnipotentem" meaning omnipotent, almighty). The implications of the difference in overtones for the interpretation of "ἐκπορευόμενον" and "qui ... procedit" was the object of the study The Greek and the Latin Traditions regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit published by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity in 1996.[32]

Again, the terms "ὁμοούσιον" and "consubstantialem", translated as "of one being" or "consubstantial", have different overtones, being based respectively on Greek οὐσία (stable being, immutable reality, substance, essence, true nature),[1] and Latin substantia (that of which a thing consists, the being, essence, contents, material, substance).[32]

"Credo", which in classical Latin is used with the accusative case of the thing held to be true (and with the dative of the person to whom credence is given),[33] is here used three times with the preposition "in", a literal translation of the Greek "εἰς" (in unum Deum ..., in unum Dominum ..., in Spiritum Sanctum ...), and once in the classical preposition-less construction (unam, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam Ecclesiam).

The versions of the Nicene Creed used in the churches of Oriental Orthodoxy preserve the plural "we believe", "we confess", "we look forward to" of the text of the First Council of Constantinople.[34] The Armenian Apostolic Church recites the Creed with many elaborations of its contents, much more numerous than the two additions in the Latin text.[6]

The Assyrian Church of the East, which is in communion neither with the Eastern Orthodox Church nor with Oriental Orthodoxy also uses "We believe".[35]

The version in the Church Slavonic language, used by several of the Eastern Orthodox Churches and of the Byzantine Rite Eastern Catholic Churches, is practically identical with the Greek liturgical version.

[edit] English translations

The version found in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer is still commonly used by some English speakers, but more modern translations are now more common.[edit] International Consultation on English Texts

The International Consultation on English Texts published an English translation of the Nicene Creed, first in 1970 and then in successive revisions in 1971 and 1975. These texts were adopted by several churches. The Roman Catholic Church in the United States, which adopted the 1971 version in 1973, and the Catholic Church in other English-speaking countries, which in 1975 adopted the version published in that year, continued to use them until 2011. The 1975 version was included in the 1979 Episcopal Church (United States) Book of Common Prayer, though with one variation: in the line "For us men and for our salvation", it omitted the word "men":- 1979 Episcopal Church (United States) Book of Common Prayer

We believe in one God,

the Father, the Almighty,

maker of heaven and earth,

of all that is, seen and unseen.We believe in one Lord, Jesus Christ,

the only Son of God,

eternally begotten of the Father,

God from God, Light from Light,

true God from true God,

begotten, not made,

of one Being with the Father.

Through him all things were made.

For us and for our salvation

he came down from heaven:

by the power of the Holy Spirit

he became incarnate from the Virgin Mary,

and was made man.

For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate;

he suffered death and was buried.

On the third day he rose again

in accordance with the Scriptures;

he ascended into heaven

and is seated at the right hand of the Father.

He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead,

and his kingdom will have no end.We believe in the Holy Spirit, the Lord, the giver of life,

who proceeds from the Father and the Son.

With the Father and the Son he is worshiped and glorified.

He has spoken through the Prophets.

We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic Church.

We acknowledge one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

We look for the resurrection of the dead,

and the life of the world to come. Amen.—Episcopal Church Book of Common Prayer (1979), The Book of Common Prayer. New York: Church Publishing Incorporated. 2007. pp. 326–327. http://library.episcopalchurch.org/assets/book_of_common_prayer.pdf#page=326. Retrieved 2013-02-18.

[edit] Other English translations

For the text of the Nicene Creed as published in 1988 by the English Language Liturgical Consultation, the successor body of the International Consultation on English Texts, see their website. For the text as recited in the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church, see the website of the Australian National Catholic Education Commission or Youcat, section 29.[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Readings in the History of Christian Theology by William Carl Placher 1988 ISBN 0-664-24057-7 pages 52-53

- ^ Jeffrey, David L. A Dictionary of biblical tradition in English literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0-8028-3634-8

- ^ Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, "Profession of Faith"

- ^ Code of Canon Law, canon 833

- ^ This version is called the Nicene Creed in Catholic Prayers, Creeds of the Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Brisbane, etc.

- ^ a b c What the Armenian Church calls the Nicene Creed is given in the Armenian Church Library, St Leon Armenian Church, Armenian Diaconate, etc.]

- ^ For instance, "Instead of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed, especially during Lent and Easter time, the baptismal Symbol of the Roman Church, known as the Apostles' Creed, may be used" (in the Roman Rite [[Mass (liturgy)|]]) (Roman Missal, Order of Mass, 19).

- ^ Philip Schaff, The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. III: article Constantinopolitan Creed lists eight creed-forms calling themselves Niceno-Constantinopolitan or Nicene.

- ^ Symbol. c.1434, "creed, summary, religious belief," from L.L. symbolum "creed, token, mark," from Gk. symbolon "token, watchword" (applied c.250 by Cyprian of Carthage to the Apostles' Creed, on the notion of the "mark" that distinguishes Christians from pagans), from syn- "together" + stem of ballein "to throw." The sense evolution is from "throwing things together" to "contrasting" to "comparing" to "token used in comparisons to determine if something is genuine." Hence, "outward sign" of something. The meaning "something which stands for something else" first recorded 1590 (in "Faerie Queene"). Symbolic is attested from 1680. (symbol. Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. Accessed: 24 March 2008).

- ^ Noll, M., "Turning Points: Decisive Moments in the History of Christianity", Inter-Varsity Press, 1997, p52

- ^ Collins. M, The Story of Christianity, Dorling Kindersley, 1999, p60

- ^ cf. Philip Schaff's The Seven Ecumenical Councils – The Nicene Creed and Creeds of Christendom: § 8. The Nicene Creed

- ^ cf. Schaff's Seven Ecumenical Councils: Second Ecumenical: The Holy Creed Which the 150 Holy Fathers Set Forth...

- ^ Schaff's Creeds: Forma Recepta Ecclesiæ Orientalis. A.D. 381, Schaff's Creeds: Forma Recepta, Ecclesiæ Occidentalis

- ^ a b c Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity: The Greek and the Latin Traditions regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit and same document on another site

- ^ a b c Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian CreedsLongmans (19602)p. 305; p.307 & pp. 322-331 respectively

- ^ Philip Schaff, The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, Vol. III: article Constantinopolitan Creed

- ^ It was the original 325 creed, not the one that is attributed to the second Ecumenical Council in 381, that was recited at the Council of Ephesus (The Third Ecumenical Council. The Council of Ephesus, p. 202).

- ^ Excursus on the Words πίστιν ἑτέραν

- ^ Canon VII of the Council of Ephesus

- ^ Excursus on the Words πίστιν ἑτέραν

- ^ See Creeds of Christendom.

The texts in Greek, as given on the Web site Symbolum Nicaeno-Constantinopolitanum – Greek, can be presented in a similar way, as follows:First Council of Nicaea (325) First Council of Constantinople (381) Πιστεύομεν εἰς ἕνα θεὸν Πατέρα παντοκράτορα, πάντων ὁρατῶν τε και ἀοράτων ποιητήν. Πιστεύομεν εἰς ἕνα θεὸν Πατέρα παντοκράτορα, ποιητὴν οὐρανοῦ καὶ γῆς, ὁρατῶν τε πάντων καὶ ἀοράτων. Πιστεύομεν εἰς ἕνα κύριον Ἰησοῦν Χριστόν, τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ θεοῦ, γεννηθέντα ἐκ τοῦ Πατρὸς μονογενῆ, τοὐτέστιν ἐκ τῆς οὐσίας τοῦ Πατρός, θεὸν ἐκ θεοῦ ἀληθινοῦ, γεννηθέντα, οὐ ποιηθέντα, ὁμοούσιον τῷ Πατρί Καὶ εἰς ἕνα κύριον Ἰησοῦν Χριστόν, τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ θεοῦ τὸν μονογενῆ, τὸν ἐκ τοῦ Πατρὸς γεννηθέντα πρὸ πάντων τῶν αἰώνων, φῶς ἐκ φωτός, θεὸν ἀληθινὸν ἐκ θεοῦ ἀληθινοῦ, γεννηθέντα οὐ ποιηθέντα, ὁμοούσιον τῷ Πατρί· δι' οὗ τὰ πάντα ἐγένετο, τά τε ἐν τῷ οὐρανῷ καὶ τὰ ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς δι' οὗ τὰ πάντα ἐγένετο· τὸν δι' ἡμᾶς τοὺς ἀνθρώπους καὶ διὰ τὴν ἡμετέραν σωτηρίαν κατελθόντα καὶ σαρκωθέντα καὶ ἐνανθρωπήσαντα, τὸν δι' ἡμᾶς τοὺς ἀνθρώπους καὶ διὰ τὴν ἡμετέραν σωτηρίαν κατελθόντα ἐκ τῶν οὐρανῶν καὶ σαρκωθέντα ἐκ Πνεύματος Ἁγίου καὶ Μαρίας τῆς παρθένου καὶ ἐνανθρωπήσαντα, παθόντα, καὶ ἀναστάντα τῇ τρίτῃ ἡμέρᾳ, καὶ ἀνελθόντα εἰς τοὺς οὐρανούς, σταυρωθέντα τε ὑπὲρ ἡμῶν ἐπὶ Ποντίου Πιλάτου, καὶ παθόντα καὶ ταφέντα, καὶ ἀναστάντα τῇ τρίτῃ ἡμέρα κατὰ τὰς γραφάς, καὶ ἀνελθόντα εἰς τοὺς οὐρανούς, καὶ καθεζόμενον ἐκ δεξιῶν τοῦ Πατρός, καὶ ἐρχόμενον κρῖναι ζῶντας καὶ νεκρούς. καὶ πάλιν ἐρχόμενον μετὰ δόξης κρῖναι ζῶντας καὶ νεκρούς· οὗ τῆς βασιλείας οὐκ ἔσται τέλος. Καὶ εἰς τὸ Ἅγιον Πνεῦμα. Καὶ εἰς τὸ Πνεῦμα τὸ Ἅγιον, τὸ κύριον, (καὶ) τὸ ζῳοποιόν, τὸ ἐκ τοῦ πατρὸς ἐκπορευόμενον, τὸ σὺν Πατρὶ καὶ Υἱῷ συμπροσκυνούμενον καὶ συνδοξαζόμενον, τὸ λαλῆσαν διὰ τῶν προφητῶν. Εἰς μίαν, ἁγίαν, καθολικὴν καὶ ἀποστολικὴν ἐκκλησίαν· ὁμολογοῦμεν ἓν βάπτισμα εἰς ἄφεσιν ἁμαρτιῶν· προσδοκοῦμεν ἀνάστασιν νεκρῶν, καὶ ζωὴν τοῦ μέλλοντος αἰῶνος. Ἀμήν. Τοὺς δὲ λέγοντας, ὅτι ἦν ποτε ὅτε οὐκ ἦν, καὶ πρὶν γεννηθῆναι οὐκ ἦν, καὶ ὅτι ἐξ οὐκ ὄντων ἐγένετο, ἢ ἐξ ἑτέρας ὑποστάσεως ἢ οὐσίας φάσκοντας εἶναι, [ἢ κτιστόν,] τρεπτὸν ἢ ἀλλοιωτὸν τὸν υἱὸν τοῦ θεοῦ, [τούτους] ἀναθεματίζει ἡ καθολικὴ [καὶ ἀποστολικὴ] ἐκκλησία. - ^ For a different view, see e.g. Excursus on the Words πίστιν ἑτέραν

- ^ See etymology given in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000

- ^ Ordo Missae, 18–19

- ^ N. R. Kehn, Scott Bayles, Restoring the Restoration Movement (Xulon Press 2009 ISBN 978-1-60791-358-0), chapter 7

- ^ Donald T. Williams, Credo (Chalice Press 2007 ISBN 978-0-8272-0505-5), pp. xiv-xv

- ^ Timothy Larsen, Daniel J. Treier, The Cambridge Companion to Evangelical Theology (Cambridge University Press 2007 9780521846981), p. 4

- ^ Dallin H. Oaks, Apostasy And Restoration, Ensign, May 1995

- ^ Stephen Hunt, Alternative Religions (Ashgate 2003 ISBN 978-0-7546-3410-2), p. 48

- ^ Charles Simpson, Inside the Churches of Christ (Arthurhouse 2009 ISBN 978-1-4389-0140-4), p. 133

- ^ a b Charlton T. Lewis, A Latin Dictionary

- ^ Lewis & Short

- ^ Nicene Creed (Armenian Apostolic Church); The Coptic Orthodox Church: Our Creed (Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria); Nicene Creed (Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church); The Nicene Creed (Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church); The Nicene Creed (Syriac Orthodox Church).

- ^ Creed of Nicaea (Assyrian Church of the East)

[edit] Bibliography

- Ayres, Lewis (2006). Nicaea and Its Legacy. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-875505-8.

- A. E. Burn, The Council of Nicaea (1925)

- G. Forell, Understanding the Nicene Creed (1965)

- Kelly, J. (1982). Early Christian Creeds. City: Longman Publishing Group. ISBN 0-582-49219-X.

First Council of Nicaea

First Council of Nicaea

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

| First Council of Nicaea | |

|---|---|

| Date | 325 AD |

| Accepted by | |

| Previous council | Council of Jerusalem (though not considered ecumenical) |

| Next council | First Council of Constantinople |

| Convoked by | Emperor Constantine I |

| Presided by | St. Alexander of Alexandria (and also Emperor Constantine)[1] |

| Attendance | 250–318 (only five from Western Church) |

| Topics of discussion | Arianism, the nature of Christ, celebration of Passover (Easter), ordination of eunuchs, prohibition of kneeling on Sundays and from Easter to Pentecost, validity of baptism by heretics, lapsed Christians, sundry other matters.[2] |

| Documents and statements | Original Nicene Creed,[3] 20 canons,[4] and an epistle[2] |

| Chronological list of Ecumenical councils | |

Its main accomplishments were settlement of the Christological issue of the nature of The Son and his relationship to God the Father,[3] the construction of the first part of the Creed of Nicaea, settling the calculation of the date of Easter,[2] and promulgation of early canon law.[4][7][8]

[edit] Overview

The First Council of Nicaea was the first ecumenical council of the Church. Most significantly, it resulted in the first, uniform Christian doctrine, called the Creed of Nicaea. With the creation of the creed, a precedent was established for subsequent local and regional councils of Bishops (Synods) to create statements of belief and canons of doctrinal orthodoxy— the intent being to define unity of beliefs for the whole of Christendom.The council settled, to some degree, the debate within the Early Christian communities regarding the divinity of Christ. This idea of the divinity of Christ, along with the idea of Christ as a messenger from God (The Father), had long existed in various parts of the Roman empire. The divinity of Christ had also been widely endorsed by the Christian community in the otherwise pagan city of Rome.[9] The council affirmed and defined what it believed to be the teachings of the Apostles regarding who Christ is: that Christ is the one true God in deity with the Father.

Derived from Greek oikoumenikos (Greek: οἰκουμένη), "ecumenical" means "worldwide" but generally is assumed to be limited to the Roman Empire in this context as in Augustus' claim to be ruler of the oikoumene/world; the earliest extant uses of the term for a council are Eusebius' Life of Constantine 3.6[10] around 338, which states "σύνοδον οἰκουμενικὴν συνεκρότει" (he convoked an Ecumenical Council); Athanasius' Ad Afros Epistola Synodica in 369;[11] and the Letter in 382 to Pope Damasus I and the Latin bishops from the First Council of Constantinople.[12]

One purpose of the council was to resolve disagreements arising from within the Church of Alexandria over the nature of the Son in his relationship to the Father; in particular, whether the Son had been 'begotten' by the Father from his own being, or created as the other creatures out of nothing.[13] St. Alexander of Alexandria and Athanasius claimed to take the first position; the popular presbyter Arius, from whom the term Arianism comes, is said to have taken the second. The council decided against the Arians overwhelmingly (of the estimated 250–318 attendees, all but two agreed to sign the creed and these two, along with Arius, were banished to Illyria).[14] The emperor's threat of banishment is claimed to have influenced many to sign, but this is highly debated by both sides.

Another result of the council was an agreement on when to celebrate Easter, the most important feast of the ecclesiastical calendar, decreed in an epistle to the Church of Alexandria in which is simply stated

We also send you the good news of the settlement concerning the holy pasch, namely that in answer to your prayers this question also has been resolved. All the brethren in the East who have hitherto followed the Jewish practice will henceforth observe the custom of the Romans and of yourselves and of all of us who from ancient times have kept Easter together with you.[15]Historically significant as the first effort to attain consensus in the church through an assembly representing all of Christendom,[5] the Council was the first occasion where the technical aspects of Christology were discussed.[5] Through it a precedent was set for subsequent general councils to adopt creeds and canons. This council is generally considered the beginning of the period of the First seven Ecumenical Councils in the History of Christianity.

[edit] Character and purpose

Constantine the Great summoned the bishops of the Christian Church to Nicea to address divisions in the Church (mosaic in Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), ca. 1000).

This was the first general council in the history of the Church since the Apostolic Council of Jerusalem, the Apostolic council having established the conditions upon which Gentiles could join the Church.[17] In the Council of Nicea, "the Church had taken her first great step to define doctrine more precisely in response to a challenge from a heretical theology."[18]

[edit] Attendees

Constantine had invited all 1800 bishops of the Christian church (about 1000 in the east and 800 in the west), but a smaller and unknown number attended. Eusebius of Caesarea counted 220,[19] Athanasius of Alexandria counted 318,[20] and Eustathius of Antioch counted 270[21] (all three were present at the council). Later, Socrates Scholasticus recorded more than 300,[22] and Evagrius,[23] Hilary of Poitiers,[24] Jerome[25] and Rufinus recorded 318. Delegates came from every region of the Roman Empire except Britain. In Ethiopic Christian literature including both the Fetha Negest and the Kibre Negest, the First Council of Nicea (Niqya) is traditionally referred to as "the three hundred and eighteen Orthodox Fathers".The participating bishops were given free travel to and from their episcopal sees to the council, as well as lodging. These bishops did not travel alone; each one had permission to bring with him two priests and three deacons; so the total number of attendees could have been above 1800. Eusebius speaks of an almost innumerable host of accompanying priests, deacons and acolytes.

A special prominence was also attached to this council because the persecution of Christians had just ended with the Edict of Milan, issued in February of AD 313 by Emperors Constantine and Licinius.

The Eastern bishops formed the great majority. Of these, the first rank was held by the three patriarchs: Alexander of Alexandria, Eustathius of Antioch, and Macarius of Jerusalem. Many of the assembled fathers—for instance, Paphnutius of Thebes, Potamon of Heraclea and Paul of Neocaesarea—had stood forth as confessors of the faith and came to the council with the marks of persecution on their faces. This position is supported by patristic scholar Timothy Barnes in his book Constantine and Eusebius.[26] Historically, the influence of these marred confessors has been seen as substantial, but recent scholarship has called this into question.[27]

Other remarkable attendees were Eusebius of Nicomedia; Eusebius of Caesarea, the purported first church historian; circumstances suggest that Nicholas of Myra attended (his life was the seed of the Santa Claus legends); Aristakes of Armenia (son of Saint Gregory the Illuminator); Leontius of Caesarea; Jacob of Nisibis, a former hermit; Hypatius of Gangra; Protogenes of Sardica; Melitius of Sebastopolis; Achilleus of Larissa (considered the Athanasius of Thessaly)[28] and Spyridion of Trimythous, who even while a bishop made his living as a shepherd.[29][30] From foreign places came John, bishop of Persia and India,[31] Theophilus, a Gothic bishop and Stratophilus, bishop of Pitiunt of Georgia.

The Latin-speaking provinces sent at least five representatives: Marcus of Calabria from Italia, Cecilian of Carthage from Africa, Hosius of Córdoba from Hispania, Nicasius of Dijon from Gaul,[28] and Domnus of Stridon from the province of the Danube.

Athanasius of Alexandria, a young deacon and companion of Bishop Alexander of Alexandria, was among the assistants. Athanasius eventually spent most of his life battling against Arianism. Alexander of Constantinople, then a presbyter, was also present as representative of his aged bishop.[28]

The supporters of Arius included Secundus of Ptolemais, Theonus of Marmarica, Zphyrius, and Dathes, all of whom hailed from the Libyan Pentapolis. Other supporters included Eusebius of Nicomedia,[32] Eusebius of Caesarea, Paulinus of Tyrus, Actius of Lydda, Menophantus of Ephesus, and Theognus of Nicea.[28][33]

"Resplendent in purple and gold, Constantine made a ceremonial entrance at the opening of the council, probably in early June, but respectfully seated the bishops ahead of himself."[17] As Eusebius described, Constantine "himself proceeded through the midst of the assembly, like some heavenly messenger of God, clothed in raiment which glittered as it were with rays of light, reflecting the glowing radiance of a purple robe, and adorned with the brilliant splendor of gold and precious stones."[34] He was present as an observer, and did not vote. Constantine organized the Council along the lines of the Roman Senate. Hosius of Cordoba may have presided over its deliberations; he was probably one of the Papal legates.[17] Eusebius of Nicomedia probably gave the welcoming address.[17][35]

[edit] Agenda and procedure

The agenda of the synod included:- The Arian question regarding the relationship between God the Father and Jesus; i.e., are the Father and Son one in divine purpose only or also one in being?

- The date of celebration of the Paschal/Easter observation

- The Meletian schism

- The validity of baptism by heretics

- The status of the lapsed in the persecution under Licinius[citation needed]

Eusebius of Caesarea called to mind the baptismal creed of his own diocese at Caesarea at Palestine, as a form of reconciliation. The majority of the bishops agreed. For some time, scholars thought that the original Nicene Creed was based on this statement of Eusebius. Today, most scholars think that the Creed is derived from the baptismal creed of Jerusalem, as Hans Lietzmann proposed.

The orthodox bishops won approval of every one of their proposals regarding the Creed. After being in session for an entire month, the council promulgated on June 19 the original Nicene Creed. This profession of faith was adopted by all the bishops "but two from Libya who had been closely associated with Arius from the beginning."[18] No historical record of their dissent actually exists; the signatures of these bishops are simply absent from the Creed.

[edit] Arian controversy

For about two months, the two sides argued and debated,[37] with each appealing to Scripture to justify their respective positions. According to many accounts, debate became so heated that at one point, Arius was slapped in the face by Nicholas of Myra, who would later be canonized.[38]

Much of the debate hinged on the difference between being "born" or "created" and being "begotten". Arians saw these as essentially the same; followers of Alexander did not. The exact meaning of many of the words used in the debates at Nicea were still unclear to speakers of other languages. Greek words like "essence" (ousia), "substance" (hypostasis), "nature" (physis), "person" (prosopon) bore a variety of meanings drawn from pre-Christian philosophers, which could not but entail misunderstandings until they were cleared up. The word homoousia, in particular, was initially disliked by many bishops because of its associations with Gnostic heretics (who used it in their theology), and because it had been condemned at the 264–268 Synods of Antioch.

[edit] Position of Arius (Arianism)

Arius maintained that the Son of God was a Creature, made from nothing; and that he was God's First Production, before all ages. And he argued that everything else was created through the Son. Thus, said the Arians, only the Son was directly created and begotten of God; and therefore there was a time that He had no existence. Arius believed the Son Jesus was capable of His own free will of right and wrong, and that "were He in the truest sense a son, He must have come after the Father, therefore the time obviously was when He was not, and hence He was a finite being,"[39] and was under God the Father. The Arians appealed to Scripture, quoting verses such as John 14:28: "the Father is greater than I", and also Colossians 1:15: "Firstborn of all creation."[edit] Position of St. Alexander

Alexander and the Nicene fathers countered the Arians' argument, saying that the Father's fatherhood, like all of his attributes, is eternal. Thus, the Father was always a father, and that the Son, therefore, always existed with him. The Nicene fathers believed that to follow the Arian view destroyed the unity of the Godhead, and made the Son unequal to the Father, in contravention of the Scriptures ("I and the Father are one"; John 10:30). Further on it says "That they all may be one; as thou, Father, art in me, and I in thee, that they also may be one in us: that the world may believe that thou hast sent me"; John 17:21.[edit] Result of the debate

The Council declared that the Son was true God, co-eternal with the Father and begotten from His same substance, arguing that such a doctrine best codified the Scriptural presentation of the Son as well as traditional Christian belief about him handed down from the Apostles. Under Constantine's influence,[40] this belief was expressed by the bishops in the Nicene Statement, which would form the basis of what has since been known as the Nicene Creed.[edit] The Nicene Creed

Main article: Nicene Creed

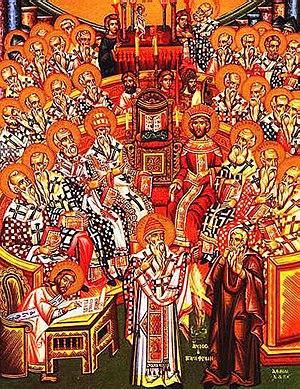

Icon depicting the Emperor Constantine and the bishops of the First Council of Nicea (325) holding the Niceno–Constantinopolitan Creed of 381.

In Rome, for example, the Apostles' Creed was popular, especially for use in Lent and the Easter season. In the Council of Nicea, one specific creed was used to define the Church's faith clearly, to include those who professed it, and to exclude those who did not.

Some distinctive elements in the Nicene Creed, perhaps from the hand of Hosius of Cordova, were added. Some elements were added specifically to counter the Arian point of view.[41] [42]

- Jesus Christ is described as "God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God," proclaiming his divinity.

- Jesus Christ is said to be "begotten, not made", asserting that he was not a mere creature, brought in to being out of nothing, but the true Son of God, brought in to being 'from the substance of the Father'.

- He is said to be "one in being with The Father". Eusebius of Caesarea ascribes the term homoousios, or consubstantial, i.e., "of the same substance" (of the Father), to Constantine who, on this particular point, may have chosen to exercise his authority. The significance of this clause, however, is extremely ambiguous, and the issues it raised would be seriously controverted in future.

- The view that 'there was once that when he was not' was rejected to maintain the co-eternity of the Son with the Father.

- The view that he was 'mutable or subject to change' was rejected to maintain that the Son just like the Father was beyond any form of weakness or corruptibility, and most importantly that he could not fall away from absolute moral perfection.

Bishop Hosius of Cordova, one of the firm Homoousians, may well have helped bring the council to consensus. At the time of the council, he was the confidant of the emperor in all Church matters. Hosius stands at the head of the lists of bishops, and Athanasius ascribes to him the actual formulation of the creed. Great leaders such as Eustathius of Antioch, Alexander of Alexandria, Athanasius, and Marcellus of Ancyra all adhered to the Homoousian position.

In spite of his sympathy for Arius, Eusebius of Caesarea adhered to the decisions of the council, accepting the entire creed. The initial number of bishops supporting Arius was small. After a month of discussion, on June 19, there were only two left: Theonas of Marmarica in Libya, and Secundus of Ptolemais. Maris of Chalcedon, who initially supported Arianism, agreed to the whole creed. Similarly, Eusebius of Nicomedia and Theognis of Nice also agreed, except for the certain statements.

The Emperor carried out his earlier statement: everybody who refused to endorse the Creed would be exiled. Arius, Theonas, and Secundus refused to adhere to the creed, and were thus exiled to Illyria, in addition to being excommunicated. The works of Arius were ordered to be confiscated and consigned to the flames while all persons found possessing them were to be executed.[14] Nevertheless, the controversy continued in various parts of the empire.[43]

The Creed was amended to a new version by the First Council of Constantinople in 381.

[edit] Separation of Easter computation from Jewish calendar

The feast of Easter is linked to the Jewish Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread, as Christians believe that the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus occurred at the time of those observances.As early as Pope Sixtus I, some Christians had set Easter to a Sunday in the lunar month of Nisan. To determine which lunar month was to be designated as Nisan, Christians relied on the Jewish community. By the later 3rd century some Christians began to express dissatisfaction with what they took to be the disorderly state of the Jewish calendar. They argued that contemporary Jews were identifying the wrong lunar month as the month of Nisan, choosing a month whose 14th day fell before the spring equinox.[44]

Christians, these thinkers argued, should abandon the custom of relying on Jewish informants and instead do their own computations to determine which month should be styled Nisan, setting Easter within this independently computed, Christian Nisan, which would always locate the festival after the equinox. They justified this break with tradition by arguing that it was in fact the contemporary Jewish calendar that had broken with tradition by ignoring the equinox, and that in former times the 14th of Nisan had never preceded the equinox.[45] Others felt that the customary practice of reliance on the Jewish calendar should continue, even if the Jewish computations were in error from a Christian point of view.[46]

The controversy between those who argued for independent computations and those who argued for continued reliance on the Jewish calendar was formally resolved by the Council, which endorsed the independent procedure that had been in use for some time at Rome and Alexandria. Easter was henceforward to be a Sunday in a lunar month chosen according to Christian criteria—in effect, a Christian Nisan—not in the month of Nisan as defined by Jews. Those who argued for continued reliance on the Jewish calendar (called "protopaschites" by later historians) were urged to come around to the majority position. That they did not all immediately do so is revealed by the existence of sermons,[47] canons,[48] and tracts[49] written against the protopaschite practice in the later 4th century.

These two rules, independence of the Jewish calendar and worldwide uniformity, were the only rules for Easter explicitly laid down by the Council. No details for the computation were specified; these were worked out in practice, a process that took centuries and generated a number of controversies. (See also Computus and Reform of the date of Easter.) In particular, the Council did not decree that Easter must fall on Sunday. This was already the practice almost everywhere.[50]

Nor did the Council decree that Easter must never coincide with Nisan 14 (the first Day of Unleavened Bread, now commonly called "Passover") in the Hebrew calendar. By endorsing the move to independent computations, the Council had separated the Easter computation from all dependence, positive or negative, on the Jewish calendar. The "Zonaras proviso", the claim that Easter must always follow Nisan 14 in the Hebrew calendar, was not formulated until after some centuries. By that time, the accumulation of errors in the Julian solar and lunar calendars had made it the de facto state of affairs that Julian Easter always followed Hebrew Nisan 14.[51]

"At the council we also considered the issue of our holiest day, Easter, and it was determined by common consent that everyone, everywhere should celebrate it on one and the same day. For what can be more appropriate, or what more solemn, than that this feast from which we have received the hope of immortality, should be kept by all without variation, using the same order and a clear arrangement? And in the first place, it seemed very unworthy for us to keep this most sacred feast following the custom of the Jews, a people who have soiled their hands in a most terrible outrage, and have thus polluted their souls, and are now deservedly blind. Since we have cast aside their way of calculating the date of the festival, we can ensure that future generations can celebrate this observance at the more accurate time which we have kept from the first day of the passion until the present time...."

— Emperor Constantine, following the Council of Nicaea[52]

[edit] Meletian schism

Main article: Meletius of Lycopolis

The suppression of the Meletian schism, an early breakaway sect, was another important matter that came before the Council of Nicea. Meletius, it was decided, should remain in his own city of Lycopolis in Egypt, but without exercising authority or the power to ordain new clergy; he was forbidden to go into the environs of the town or to enter another diocese for the purpose of ordaining its subjects. Melitius retained his episcopal title, but the ecclesiastics ordained by him were to receive again the Laying on of hands, the ordinations performed by Meletius being therefore regarded as invalid. Clergy ordained by Meletius were ordered to yield precedence to those ordained by Alexander, and they were not to do anything without the consent of Bishop Alexander.[53]In the event of the death of a non-Meletian bishop or ecclesiastic, the vacant see might be given to a Meletian, provided he was worthy and the popular election were ratified by Alexander. As to Meletius himself, episcopal rights and prerogatives were taken from him. These mild measures, however, were in vain; the Meletians joined the Arians and caused more dissension than ever, being among the worst enemies of Athanasius. The Meletians ultimately died out around the middle of the fifth century.

[edit] Promulgation of canon law

The council promulgated twenty new church laws, called canons, (though the exact number is subject to debate[54]), that is, unchanging rules of discipline. The twenty as listed in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers are as follows:[55]- 1. prohibition of self-castration

- 2. establishment of a minimum term for catechumen (persons studying for baptism)

- 3. prohibition of the presence in the house of a cleric of a younger woman who might bring him under suspicion (the so called virgines subintroductae)

- 4. ordination of a bishop in the presence of at least three provincial bishops and confirmation by the Metropolitan bishop

- 5. provision for two provincial synods to be held annually

- 6. exceptional authority acknowledged for the patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch, and Rome (the Pope), for their respective regions

- 7. recognition of the honorary rights of the see of Jerusalem

- 8. provision for agreement with the Novatianists, an early sect

- 9–14. provision for mild procedure against the lapsed during the persecution under Licinius

- 15–16. prohibition of the removal of priests

- 17. prohibition of usury among the clergy

- 18. precedence of bishops and presbyters before deacons in receiving the Eucharist (Holy Communion)

- 19. declaration of the invalidity of baptism by Paulian heretics

- 20. prohibition of kneeling on Sundays and during the Pentecost (the fifty days commencing on Easter). Standing was the normative posture for prayer at this time, as it still is among the Eastern Christians.[56]

[edit] Effects of the Council

The long-term effects of the Council of Nicea were significant. For the first time, representatives of many of the bishops of the Church convened to agree on a doctrinal statement. Also for the first time, the Emperor played a role, by calling together the bishops under his authority, and using the power of the state to give the Council's orders effect.In the short-term, however, the council did not completely solve the problems it was convened to discuss and a period of conflict and upheaval continued for some time. Constantine himself was succeeded by two Arian Emperors in the Eastern Empire: his son, Constantius II and Valens. Valens could not resolve the outstanding ecclesiastical issues, and unsuccessfully confronted St. Basil over the Nicene Creed.[57]

Pagan powers within the Empire sought to maintain and at times re-establish paganism into the seat of the Emperor (see Arbogast and Julian the Apostate). Arians and Meletians soon regained nearly all of the rights they had lost, and consequently, Arianism continued to spread and to cause division in the Church during the remainder of the fourth century. Almost immediately, Eusebius of Nicomedia, an Arian bishop and cousin to Constantine I, used his influence at court to sway Constantine's favor from the orthodox Nicene bishops to the Arians.[58]

Eustathius of Antioch was deposed and exiled in 330. Athanasius, who had succeeded Alexander as Bishop of Alexandria, was deposed by the First Synod of Tyre in 335 and Marcellus of Ancyra followed him in 336. Arius himself returned to Constantinople to be readmitted into the Church, but died shortly before he could be received. Constantine died the next year, after finally receiving baptism from Arian Bishop Eusebius of Nicomedia, and "with his passing the first round in the battle after the Council of Nicea was ended."[59]

[edit] Misconceptions

| This section's listed sources may not meet Wikipedia's guidelines for reliable sources. Please help by checking whether the references meet the criteria for reliable sources. (February 2012) |

[edit] The biblical canon

Main article: Development of the Christian biblical canon

A number of erroneous views have been stated regarding the council's role in establishing the biblical canon. In fact, there is no record of any discussion of the biblical canon at the council at all.[60][61] The development of the biblical canon took centuries, and was nearly complete (with exceptions known as the Antilegomena, written texts whose authenticity or value is disputed) by the time the Muratorian fragment was written.[62]In 331 Constantine commissioned fifty Bibles for the Church of Constantinople, but little else is known, though it has been speculated that this may have provided motivation for canon lists. In Jerome's Prologue to Judith[63][64][65] he claims that the Book of Judith was "found by the Nicene Council to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures".

[edit] The Trinity

The council of Nicea dealt primarily with the issue of the deity of Christ. Over a century earlier the use of the term "Trinity" (Τριάς in Greek; trinitas in Latin) could be found in the writings of Origen (185-254) and Tertullian (160-220), and a general notion of a "divine three", in some sense, was expressed in the second century writings of Polycarp, Ignatius, and Justin Martyr. In Nicaea, questions regarding the Holy Spirit were left largely unaddressed until after the relationship between the Father and the Son were settled around the year 362.[66] So the doctrine in a more full-fledged form was not formulated until the Council of Constantinople in 360 AD.[67][edit] The role of Constantine

Main article: Constantine I and Christianity

While Constantine wanted a unified church after the council for political reasons, he did not force the Homoousian view of Christ's nature on the council, nor commission a Bible at the council that omitted books he did not approve of, although he did later commission Bibles. In fact, Constantine had little theological understanding of the issues at stake, and did not particularly care which view of Christ's nature prevailed so long as it resulted in a unified church.[68] This can be seen in his initial acceptance of the Homoousian view of Christ's nature, only to abandon the belief several years later for political reasons; under the influence of Eusebius of Nicomedia and others.[68]Despite Constantine's sympathetic interest in the future of the Church, he did not actually undergo the rite of baptism himself until some 11 or 12 years afterward. Christianity at this point had been legalized (by Constantine's predecessor, Galerius, on his deathbed), but was not to become the official state religion of Rome until 380. Constantine's coinage and other motifs, until the time of this Council, had affiliated him with the pagan cult of Sol Invictus, and only four years before Nicea, Constantine had declared Sunday to be an Empire-wide day of rest in honor of the Sun, which led to its replacement of Saturday as the sabbath in European Christendom.

For more details on this topic, see Constantine I's turn against Paganism.

[edit] Disputed matters

[edit] The role of the Bishop of Rome

See also: Primacy of the Roman pontiff and East-West Schism

Roman Catholics assert that the idea of Christ's deity was ultimately confirmed by the Bishop of Rome, and that it was this confirmation that gave the council its influence and authority. In support of this, they cite the position of early fathers and their expression of the need for all churches to agree with Rome (see Ireneaus, Adversus Haereses III:3:2).However, Protestants and Eastern Orthodox do not believe the Council viewed the Bishop of Rome as the jurisdictional head of Christendom, or someone having authority over other bishops attending the Council. In support of this, they cite Canon 6, where the Roman Bishop could be seen as simply one of several influential leaders, but not one who had jurisdiction over other bishops in other regions.

According to Protestant theologian Philip Schaff, "The Nicene fathers passed this canon not as introducing anything new, but merely as confirming an existing relation on the basis of church tradition; and that, with special reference to Alexandria, on account of the troubles existing there. Rome was named only for illustration; and Antioch and all the other eparchies or provinces were secured their admitted rights. The bishoprics of Alexandria, Rome, and Antioch were placed substantially on equal footing"[70]"Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya, and Pentapolis prevail: that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges..."[69]

There is however, an alternate Roman Catholic interpretation of the above 6th canon proposed by Fr. James F. Loughlin in contradistinction to the above interpretation; an interpretation which is in line with the above reference from Ireneaus. It involves five different arguments "drawn respectively from the grammatical structure of the sentence, from the logical sequence of ideas, from Catholic analogy, from comparison with the process of formation of the Byzantine Patriarchate, and from the authority of the ancients"[71] in favor of an alternative understanding of the canon. The understanding of the canon according to Fr. Loughlin can be summarized as follows:

"Let the Bishop of Alexandria continue to govern these provinces, because this is also the Roman Pontiff's custom; that is, because the Roman Pontiff, prior to any synodical enactment, has repeatedly recognized the Alexandrian Bishop's authority over this tract of country".[71]

According to this interpretation, the canon shows the role the Bishop of Rome had when he, by his authority, confirmed the jurisdiction of the other patriarchs- an interpretation which is in line with the Roman Catholic understanding of the Pope.

[edit] See also

[edit] Bibliography

[edit] Primary sources

- Schaff, Philip; Wace, Henry, eds. (1890). The Seven Ecumenical Councils. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: Second Series. 14, The Seven Ecumenical Councils. Grand Rapids, Michigan, U.S.A.: Eerdmans Pub Co.. ISBN 0-8028-8129-7. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf214.html

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Letter of Eusebius of Cæsarea to the people of his Diocese Account of the Council of Nicea; The Life of the Blessed Emperor Constantine Book 3, Chapters VI-XXI treat the First Council of Nicea.

- Athanasius of Alexandria, Defence of the Nicene Definition; Ad Afros Epistola Synodica

- Eustathius of Antioch, Letter recorded in Theodoret H.E. 1.7

- Socrates, Of the Synod which was held at Nicæa in Bithynia, and the Creed there put forth Book 1 Chapter 8 of his Ecclesiastical History, 5th century source.

- Sozomen, Of the Council convened at Nicæa on Account of Arius Book 1 Chapter 17 of his Ecclesiastical History, a 5th century source.

- Theodoret, General Council of Nicæa Book 1 Chapter 6 of his Ecclesiastical History; The Epistle of the Emperor Constantine, concerning the matters transacted at the Council, addressed to those Bishops who were not present Book 1 Chapter 9 of his Ecclesiastical History, a 5th century source;

- Philostorgius, Epitome of the Church History.

[edit] Literature

- Ayres, Lewis, Nicaea and Its Legacy, 2004, ISBN 0-19-875505-8

- Carroll, Warren H., The Building of Christendom, 1987, ISBN 0-931888-24-7

- Davis, S.J., Leo Donald, The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787), 1983, ISBN 0-8146-5616-1

- Kelly, J.N.D., The Nicene Crisis in Early Christian Doctrines, 1978, ISBN 0-06-064334-X

- Kelly, J.N.D., The Creed of Nicea in Early Christian Creeds, 1982, ISBN 0-582-49219-X

- MacMullen, Ramsay. Voting About God in Early Church Councils, Yale University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-300-11596-2

- Newman, John Henry., The Ecumenical Council of Nicæa in the Reign of Constantine from Arians of the Fourth century, 1871

- Rubenstein, Richard E., When Jesus Became God: The Epic Fight Over Christ's Divinity in the Last Days of Rome, 2003, ISBN 0-15-100368-8

- Rusch, William G. "The Trinitarian Controversy", Sources of Christian Thought Series, ISBN 0-8006-1410-0

- Schaff, Philip The first ecumenical council includes creed and canons of the council.

- Tanner S.J., Norman P., "The Councils of the Church: A Short History", 2001, ISBN 0-8245-1904-3

- Williams, Rowan. Arius: Heresy and Tradition, Darton, Longman & Todd Ltd, 1987, ISBN 0-232-51692-8

[edit] References

- ^ Britannica.com - Council of Nicaea

- ^ a b c The Seven Ecumenical Councils:112-114

- ^ a b The Seven Ecumenical Councils:39

- ^ a b The Seven Ecumenical Councils:44-94

- ^ a b c Richard Kieckhefer (1989). "Papacy". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. ISBN 0-684-18275-0.

- ^ The very first church council is recorded in the book of Acts chapter 15 regarding circumcision.

- ^

"First Council of Nicea" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

"First Council of Nicea" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia. - ^ "Council of Nicea in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica". www.1911encyclopeida.org. http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Council_of_Nicaea. Retrieved march 14, 2010.

- ^ Newman, A. H.. A Manual of Church History, D.D.LL.D., Vol. I. p. 330. http://www.archive.org/stream/amanualchurchhi05newmgoog/amanualchurchhi05newmgoog_djvu.txt. "Describing the proceedings of the Nicene Council: "Eusebius of Caesarea then proposed an ancient Palestinian creed, which acknowledged the divine nature of Christ in general biblical terms. The emperor had already expressed a favorable opinion of this creed. The Arians were willing to subscribe to it, but this latter fact made the Athanasian party suspicious. They wanted a creed that no Arian could subscribe, and insisted on inserting the term identical in substance (Greek: ὁμοούσιος, from the Greek: ὁμός, homós, "same" and οὐσία, ousía, "essence, being")." (Emphasis added)."

- ^ Winkelmann, F, ed. (1975) (in Greek). Vita Constantini. Berlin, DE: Akademie-Verlag. http://khazarzar.skeptik.net/books/eusebius/vc/gr/.

- ^ Ninety Bishops of Egypt and Libya, including Athanasius (1892). Schaff, Philip; Knight, Kevin. eds. Ad Afros Epistola Synodica. Archibald Robertson (transl.). Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2819.htm

- ^ The Seven Ecumenical Councils:292-294

- ^ J.N.D Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, Chapter 9.

- ^ a b "§ 120. The Council of Nicea, 325". Schaff's History of the Christian Church, Volume III, Nicene and Post-Nicene Christianity,. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/hcc3.iii.xii.iv.html. "Only two Egyptian bishops, Theonas and Secundus, persistently refused to sign, and were banished with Arius to Illyria. The books of Arius were burned and his followers branded as enemies of Christianity."

- ^ The Seven Ecumenical Councils:114

- ^ Carroll, 10

- ^ a b c d e Carroll, 11

- ^ a b Carroll, 12

- ^ Eusebius of Caesaria. "Life of Constantine (Book III)". pp. Chapter 9. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/25023.htm. Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- ^ Ad Afros Epistola Synodica 2

- ^ Theodoret H.E. 1.7

- ^ H.E. 1.8

- ^ H.E. 3.31

- ^ Contra Constantium

- ^ Chronicon

- ^ Barnes, Timothy (1981). Constantine and Eusebius. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 214–215. ISBN 0674165306.

- ^ Kelhoffer, James (Winter 2011). "The Search for Confessors at the Council of Nicaea". Journal of Early Christian Studies (Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press) 19 (4): 589–599. doi:10.1353/earl.2011.0053.

- ^ a b c d Atiya, Aziz S.. The Coptic Encyclopedia. New York:Macmillan Publishing Company, 1991. ISBN 0-02-897025-X.

- ^ [1] "Tremithus — From the Catholic Encyclopedia", Retrieved 2011-11-14

- ^ [2] "The Life of St Spyridon — St Spyridon - Australia", Retrieved 2011-11-14

- ^ http://www.oxuscom.com/ch-of-east.htm

- ^ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 1, chapter 9.

- ^ Philostorgius, in Photius, Epitome of the Ecclesiastical History of Philostorgius, book 1, chapter 9.

- ^ Eusebius, The Life of the Blessed Emperor Constantine, Book 3, Chapter 10.

- ^ Original lists of attendees can be found in Patrum Nicaenorum nomina Latine, Graece, Coptice, Syriace, Arabice, Armeniace, ed. Henricus Gelzer, Henricus Hilgenfeld, Otto Cuntz. 2nd edition. (Stuttgart: Teubner, 1995)

- ^ J.N.D Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, Chapter 9.

- ^ "Babylon the Great Has Fallen!" - God's Kingdom Rules! - Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc., 1963, pg 477

- ^ Bishop Nicholas Loses His Cool at the Council of Nicea. From the St. Nicholas center. See also St. Nicholas the Wonderworker, from the website of the Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved on 2010-02-02.

- ^ M'Clintock and Strong's Cyclopedia, Volume 7, page 45a

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1971, Volume 6, page 386

- ^ Loyn, H. R. (1989). The Middle Ages: A Concise Encyclopædia. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd.. p. 240. ISBN 0-500-27645-5.

- ^ J.N.D Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines, Chapter 9.

- ^ von Padberg, Lutz (1998) (in German), Die Christianisierung Europas Im Mittelalter [The Christianization of Europe in the Middle Ages], Leipzig: Reclam, p. 26, ISBN 978-3-15-017015-1, http://books.google.com/books?id=s0HFQAAACAAJ, retrieved 16 January 2013

- ^ "Those who place [the first lunar month of the year] in [the twelfth zodiacal sign before the spring equinox] and fix the Paschal fourteenth day accordingly, make a great and indeed an extraordinary mistake", Anatolius of Laodicea, quoted in Eusebius, Church History 7.32.

- ^ "On the fourteenth day of [the month], being accurately observed after the equinox, the ancients celebrated the Passover, according to the divine command. Whereas the men of the present day now celebrate it before the equinox, and that altogether through negligence and error", Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, quoted in the Chronicon Paschale

- ^ A version of the Apostolic Constitutions used by the sect of the Audiani advised: "Do not do your own computations, but instead observe Passover when your brethren from the circumcision do. If they err [in the computation], it is no matter to you...." Epiphanius, Panarion 3.1.10 (Heresy #70, 10,1), PG 42,355-360. Frank Williams, ed., The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis Books II and III, Leiden, E.J. Brill, 1994, p. 412. Also quoted in Margaret Dunlop Gibson, The Didascalia Apostolorum in Syriac, London, 1903, p. vii.

- ^ St. John Chrysostom, "Against those who keep the first Passover", in Saint John Chrysostom: Discourses against Judaizing Christians, translated by Paul W. Harkins, Washington, D.C., 1979, p. 47ff.

- ^ Apostolic Canon 7: If any bishop, presbyter, or deacon shall celebrate the holy day of Easter before the vernal equinox with the Jews, let him be deposed. A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Eerdmans, 1956, p. 594

- ^ Epiphanius of Salamis, "Against the Audians", Panairion 3.1 (Heresy #70), PG 42, 339. Frank Williams, ed., The Panarion of Epiphanius of Salamis Books II and III, Leiden, 1994, p. 402.

- ^ The Quartodeciman practice recorded by Eusebius in the late 2nd century, if it still existed at the time of the Council, is not known to have been followed outside the Roman Province of Asia. The Pepuzites, or "solar quartodecimans", held Easter on the Sunday falling in the week of April 6th, Sozomen, Church History, 7.18.

- ^ Peter L'Huillier, The Church of the Ancient Councils, St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, Crestwood, 1996, p. 25.

- ^ "Emperor Constantine to All Churches Concerning the Date of Easter". fourthcentury.com. 2010-01-23. http://www.fourthcentury.com/index.php/urkunde-26. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ^

"Meletius" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia.

"Meletius" in the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia. - ^ "Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series II, Vol. XIV, Excursus on the Number of the Nicene Canons". Early Church Fathers. http://www.ccel.org/fathers2/NPNF2-14/Npnf2-14-24.htm#TopOfPage. Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- ^ "Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Series II, Vol. XIV, The Canons of the 318 Holy Fathers Assembled in the City of Nice (sic), in Bithynia.". Early Church Fathers. http://www.ccel.org/fathers2/NPNF2-14/Npnf2-14-13.htm#P561_131414. Retrieved 2006-05-08.

- ^ In time, Western Christianity adopted the term Pentecost to refer to the last Sunday of Eastertide, the fiftieth day. For the exact text of the prohibition of kneeling, in Greek and in English translation, see canon 20 of the acts of the council.

- ^ "Heroes of the Fourth Century". http://www.orthodoxresearchinstitute.org/articles/patrology/heroes_of_4th_century_pt2.htm.

- ^ Leo Donald Davis, S.J., "The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787)", 77, ISBN 0-8146-5616-1

- ^ Leo Donald Davis, S.J., "The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787)", 77, ISBN 0-8146-5616-1

- ^ Ehrman, Bart. Fact and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code, pp. 15-16, 23, 93

- ^ Nicea Myths: Common Fables About The Council of Nicea and Constantine. Retrieved on 2010-08-20.

- ^ McDonald & Sanders' The Canon Debate, Appendix D-2, note 19: "Revelation was added later in 419 at the subsequent synod of Carthage." "Two books of Esdras" is ambiguous, it could be 1 Esdras and Ezra-Nehemiah as in the Septuagint or Ezra and Nehemiah as in the Vulgate.

- ^ http://www.bombaxo.com/blog/?p=224

- ^ CCEL.ORG: Schaff's Nicene and Post=Nicene Fathers: Jerome: Prologue to Tobit and Judith

- ^

"Book of Judith". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.: Canonicity: "..."the Synod of Nicaea is said to have accounted it as Sacred Scripture" (Praef. in Lib.). It is true that no such declaration is to be found in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether St. Jerome is referring to the use made of the book in the discussions of the council, or whether he was misled by some spurious canons attributed to that council"

"Book of Judith". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.: Canonicity: "..."the Synod of Nicaea is said to have accounted it as Sacred Scripture" (Praef. in Lib.). It is true that no such declaration is to be found in the Canons of Nicaea, and it is uncertain whether St. Jerome is referring to the use made of the book in the discussions of the council, or whether he was misled by some spurious canons attributed to that council" - ^ Fairbairn, Donald (2009), Life in the Trinity, Downers Grove: Intervarsity Press, pp. 46–47, ISBN 978-0-8308-3873-8

- ^ Zenos' translated edition of Socrates Scholasticus, Church History, book 2, chapter 41.

- ^ a b "What Really Happened at Nicea?". Equip.org. http://www.equip.org/articles/what-really-happened-at-nicea-. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- ^ Prof. John P. Adams, Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures (2010-01-24). "The Ecumenical Council, Nicea A.D. 325". Csun.edu. http://www.csun.edu/~hcfll004/nicea.html. Retrieved 2010-08-20.[dead link]

- ^ Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church, vol. 3, pp. 275-276

- ^ a b Fr. James F. Loughlin. American Catholic Quarterly Review (volume 5, 1880), pages 220-239 -- copyright (c) 1997, Classica Media, Inc

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)